Which is more important: the artistic merit of Nietzsche’s writing, or its philosophical content? A similar question could be asked about Plato. Dialogues such as the Apology and Republic are works of art that also convey philosophical arguments.

Let’s take a look at a passage from The Anti-Christ §11. (I’ve compressed it a bit.)

A word now against Kant as a moralist. A virtue must be our invention; it must spring out of our personal need and defence. In every other case it is a source of danger. That which does not belong to our life menaces it; a virtue which has its roots in mere respect for the concept of “virtue,” as Kant would have it, is pernicious. Quite the contrary is demanded by the most profound laws of self-preservation and of growth: to wit, that every man find his own virtue, his own categorical imperative. Nothing works a more complete and penetrating disaster than every “impersonal” duty, every sacrifice before the Moloch of abstraction.

An action prompted by the life-instinct proves that it is a right action by the amount of pleasure that goes with it: and yet that Nihilist, with his bowels of Christian dogmatism, regarded pleasure as an objection…. What destroys a man more quickly than to work, think and feel without inner necessity, without any deep personal desire, without pleasure – as a mere automaton of duty? That is the recipe for décadence, and no less for idiocy…. Kant became an idiot.– This calamitous spinner of cobwebs passed for the German philosopher – still passes today!… I forbid myself to say what I think of the Germans…. Instinct at fault in everything and anything, instinct as a revolt against nature, German décadence as a philosophy – that is Kant! —

If we think only of the argument here, it’s an interesting one. Nietzsche’s criticism of Kant’s moral philosophy is reminiscent of Hegel’s: an abstract rule offers insufficient guidance when it comes to concrete action. But Nietzsche is saying something more. His idea is that doing the right thing because one feels compelled to do it, on the basis of an abstract and impersonal moral law, impoverishes one’s soul. You become both guilt-ridden, fearing that you’ve failed to do your duty, and a scold, accusing others of failing to do theirs. A better approach, Nietzsche is saying, would regard doing the right thing as a passion, something keenly desired whose achievement would bring pleasure.

This is all very interesting and important, but as a philosophical argument it’s no more than the very beginning of a discussion. Nietzsche describes a concept and offers a counter-concept. There’s nothing about the ins and outs of the debate that must take place about them.

On the other hand, look at how he describes the two positions, and how he expresses his support for one and rejection of the other!

First, everything is presented personally. We feel as if Nietzsche is speaking directly to us. And he speaks dramatically: Kant’s moral theory is dangerous to our well-being and threatens our very lives. The “Moloch of abstraction” – a wonderful image – turns us into unfeeling robots. The conclusion is shocking, even offensive: “Kant became an idiot.”

There is also the characterization of Kant as a “spinner of cobwebs,” another vivid image. Kant claims to offer a web of concepts organized into a coherent whole. But as the threads accumulate, they tangle and become confusing and disorienting, the web becomes a cobweb, and Kant’s concepts become distinctions without differences that lead one away from real life.

Whether you find any of this plausible or interesting, it’s impossible not to be fascinated by the speaker. Who is he? What does he stand for? To what has he devoted his prodigious stylistic gifts? What does he want from us?

From this point of view it’s beginning to look like Nietzsche’s literary merit exceeds his philosophical merit. But that presumes that philosophy is nothing but argument.

It isn’t, and never has been. Plato wrote dramatic dialogues. Aristotle left us lecture notes. Augustine confessed. Machiavelli wrote an advice manual. Tocqueville wrote a travel book. Wittgenstein carried out investigations.

The voice of the philosopher is determined in part by the quality of his or her arguments, but what awakens us to their importance is very often the personality of the philosopher.

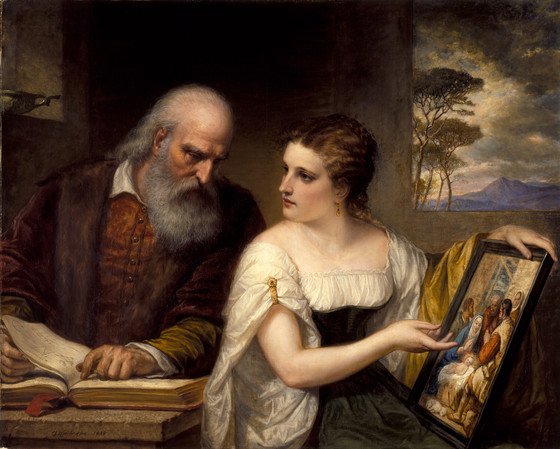

Below, Daniel Huntington, Philosophy and Christian Art.