Myth is “already” enlightenment because myth and enlightenment have something in common: the desire to control nature, rooted in a fear of nature and aggression.

In myth and religion, human beings tried to control nature (at least to the extent of sustaining the right amounts sun, rain, and fertility) by propitiating the gods, offering them sacrifices and other signs of devotion. Myth and religion understood nature in personal terms, seeing in forces such as sun, rain, and wind the recognizably human qualities of purpose and desire. Knowledge of reality was acquired by means of inspired mystical experiences, and passed down through the generations as authorized by tradition.

The central principle of the Enlightenment, on the other hand, was the sovereignty of reason. Reason is the highest source of intellectual authority, and its findings trump religion and tradition. Reason establishes the value of religion and tradition, but neither religion nor tradition can evaluate reason. As Immanuel Kant put it in the Critique of Pure Reason (1781):

Our age is, to a preeminent degree, the age of criticism, and to criticism everything must submit. Religion through its sanctity, and the state through its majesty, may seek to exempt themselves from it. But then they arouse just suspicion against themselves, and cannot claim the sincere respect which reason gives only to that which sustains the test of free and open examination. (Critique of Pure Reason A.xii.)

Whereas myth and religion acquired knowledge by revelation and tradition, the Enlightenment held that knowledge is acquired by the use of reason. Whereas myth and religion discerned divine personalities behind natural events, the Enlightenment viewed nature coldly and impersonally, investigating the world objectively and searching for universal “laws of nature.” These laws are established by appealing to arguments and evidence, grounded in careful observation, that any rational person can understand and evaluate for him- or herself.

Myth and religion are “already enlightened” because, like science, they express the desire to control nature. But enlightenment is “still mythical” precisely because it too is an expression of the desire to control nature. The desire to reduce things and events in the real world to “instances” of abstract laws that “govern” nature is at bottom an aggressive impulse. Both myth and enlightenment fear nature and are alienated from it.

The most gruesome form this takes is fear of and alienation from human nature. Human beings wish to exercise control not only over external nature, but also over themselves. This can mean dominating and exploiting others, but it can also take the form of the individual’s control over his or her own passions and desires. This is accomplished by repressing them. The psychological suffering required is intense and debilitating and greatly narrows human feeling, especially the capacities of empathy, openness, and spontaneity. We become, in Herbert Marcuse’s nomenclature, “one-dimensional.”

Approaching life rationally – and putting our knowledge of the laws of nature to use in the form of technology – enables us to organize society more effectively and make life more secure, but only because our obsessive-compulsive and paranoid drive to render the world predictable and useful has transformed us into predictable and useful instruments. Our needs are more reliably satisfied, but the needs themselves are limited to those for basic physiological necessities and protection from injury. The higher functions of personality development atrophy.

Enlightenment, therefore, is still mythological in the sense that it is incompletely rational. It is rational in the sense of efficiency, constantly improving the means to our ends. But it fails to reflect on the ends themselves. Eventually the only end recognized is the improvement of means, and we come to see ourselves as mere instruments whose only purpose is to more fully “instrumentalize” the world.

The alternative envisioned by Horkheimer and Adorno is to revive what the former called substantive reason, the faculty that enables us to deliberate over what constitutes human happiness or the best way of life for humans. In this way, enlightenment becomes critical of itself as well as of myth, religion, tradition, and authority.

Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947) is the locus classicus for this train of thought, but its elements were developed long before the book was written. The idea that reason is self-reflective or self-critical, and that reason is not as authoritative as the Enlightenment claimed, arose in 18th century Germany with the work of Johann Feuerbach (1775-1833), Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (1743-1819), and Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) among others. All these thinkers argued that the premises of the Enlightenment, when properly understood, undermined the Enlightenment itself by calling into question its own moral and political commitments, e.g. to freedom and equality.[5]

Horkheimer and Adorno drew mainly on later thinkers, above all Nietzsche, Marx, Weber, and Freud. Yet another source of the idea that there is continuity between myth and enlightenment is James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890/1915).

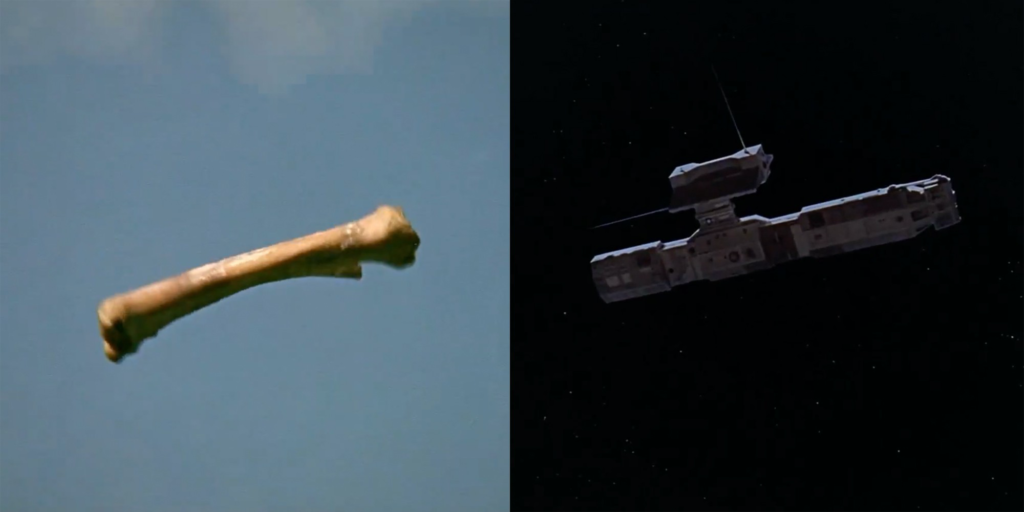

Below, what’s changed and what hasn’t in 4 million years: a representation of Stanley Kubrick’s match cut in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).