I’ve been teaching a course on philosophy and film. As it nears the end, I’m thinking about films that didn’t make it into the course but that could have and perhaps should have. This version of the course (I’ve taught it a few times) focused on the problem of identity and moral personhood: numerical identity in Inception and Solaris, for example, and differences between persons and what Harry Frankfurt calls “wantons” in A Clockwork Orange, The Servant, and Vertigo, among others. We tended to focus more on content than form, but we were never very far from issues of truth, reality, and the art of film.

Which made me want to identify films that bring these epistemological and ontological themes in both life and art together with personhood. In the films of Stanley Kubrick, there’s something of a dialectic between truthfulness and realism. Realism can reveal truth but also obscure it, and be obscured by it. And “realistic” isn’t the right word for the film I have in mind; “truthful” is closer to the mark. Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999) portrays intimate personal relationships truthfully. What does that mean?

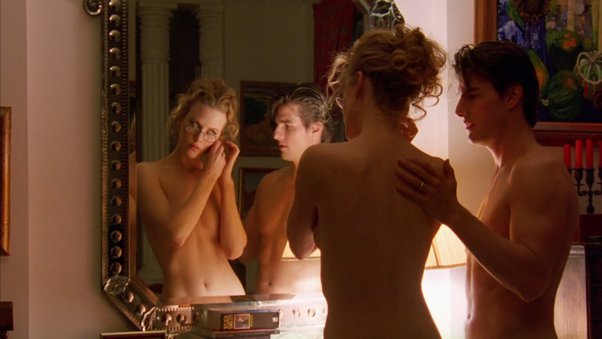

The film is about a couple, Alice and Bill, who, although they’ve been married at least seven years, still seem to be adjusting to the transition from passionate love to a companionate marriage. When we first see them, as they are preparing to leave for a Christmas party, they are very much in the companionate mode: intimate and trusting, but something less than passionate.

When Bill mechanically replies “It’s great” to Alice’s question about whether her hair is okay, she points out that he’s “not even looking at it.” Bill’s comeback – “You always look beautiful” – although cheerfully delivered, carries the melancholy implication that Alice’s attractiveness is now so routine that he is not much affected by it.

One aspect of the adjustment to companionate love is learning to manage the nostalgia for romantic love. The core fantasy concerns a return to the moment the beloved was still something of a stranger, with an air of mystery and the excitement associated with risking the unknown and unpredictable. Alice and Bill seem to be trying, rather clumsily and with little self-awareness (but probably no less than is typical), to accomplish this return in a way that accommodates their marriage, and the party conveniently provides them with opportunities to flirt with strangers and make each other jealous.

After the party, in a scene accompanied by Chris Isaak’s song “Baby Did a Bad Bad Thing,” Alice and Bill find themselves in a heightened state of arousal. The party has “worked.” They don’t discuss it; they merely act on their desires.

This scene foreshadows the end of the film, when Bill and Alice self-consciously acknowledge the persistence of one another’s romantic qualities of mystery, strangeness, and unpredictability while also – given the destructive ways these qualities have been expressed – gaining a renewed appreciation of the familiarity and reliability of their marriage.

The next day and evening, the couple are back to their companionate routine. But during what looks like a standard prelude to lovemaking, Alice confesses a sexual fantasy, provoked by a single exchange of glances with a Naval officer during a recent vacation at Cape Cod, so powerful that she would have left their marriage in order to consummate it. Waking up with Bill the morning after she saw the man, Alice “didn’t know whether [she] was afraid that he had left or that he might still be there.” When it was clear that he had left, Alice tells Bill, “I was relieved.”

Much of the rest of Eyes Wide Shut is driven by Bill’s attempts both to understand his wife’s fantasy and to exploit opportunities to enact his own version of it, neither of which succeeds.

I won’t go into the events that follow, but the important point for the question about the truthful portrayal of love is that everything we see is rigorously ambiguous. It’s impossible for the viewer to sort out what really happened from what appeared to have happened, what was said to have happened, what was believed to have happened, and what was feared to have happened. Intentions, motives, aims, and events simply cannot be fixed. In this respect, the film is a faithful depiction of real life (and love), and it’s one reason some viewers are frustrated by it: one of the things we most want from art is a clarity that reality doesn’t deliver. For the sake of genuine realism, Kubrick denies us that satisfaction.

In doing so, he lets us see some important features of truth, at least in so far as the concept applies to persons and their desire for knowledge of one another – and their fear of it. For one, truths about persons require personal involvement, hence vulnerability and exposure to risk. For another, although truth is holistic, it emerges from a series or constellation of partial views, and returns to them. By the time we understand something about a person, the moment at which it might have made a difference has often passed. Finally, personal understanding requires understanding one another’s fantasies, fears, and hopes – an especially important sense in which truthfulness and reality don’t necessarily coincide. All these characteristics apply not only to truth but also to the story Eyes Wide Shut tells, and to the film itself. That’s the larger sense in which the film is truthful.

The film’s pivotal event is the all-night conversation between Bill and Alice. Since that is what somehow enables them to move on together, it’s the one scene that could only have been depicted unambiguously – so Kubrick wisely omitted it, leaving the viewer with the impossible task of imagining the inner workings of someone else’s marriage.

A personal relationship is an imbroglio that is held together not by belief but by will, as Alice makes very clear at the end of the film. The ending is also unambiguous. Alice brings the story to a close by famously using one word to indicate that she and Bill should deal with their “adventures” exactly the same way they dealt with the energies activated at the Christmas party. She brings the story full circle, and reveals the circular nature of desire and satisfaction, as unequivocally as has ever been done in a work of art.

…speaking of banal, and I know this is tangental, but I will never forgive Kubrick for making a parade of feminine nudity so incredibly boring. I suspect this was deliberate considering it’s the work of a master filmmaker, but come on! What a waste. So satisfaction is EXACTLY the thing Kubrick denies us! For me this film was superficial, a vehicle for the two leads in their youthful prime portrayed by a master artist, far from his own. Kubrick bridles human sexuality, governs it, dominates it, and presents a film that is as far away from truth as it is from fantasy. This realm of gray is for our real lives, not a good look for a master artist.

There is nothing much real in *Eyes Wide Shut* but there is plenty of truth. We enter the film as we enter cinema. The lights are out, but the images are on. A dream. As his last film, EWS turns out to be Kubrick’s exploration of cinema’s truth. Not realism, but the truth of closed eyes. We slip from reality into dream, as we move from the Harfords’ apartment to the party and later into the darker recesses of the night in NYC’s realm of power and eros. All along, Bill is enticed, but steps back from what his instinctual demands. When his dark night is over, he and his wife share what they think they want in their dream visions of eros, but then they return to the light. The night is over, and the cinema is complete. The house lights come on. And life, real life, is refreshed by a journey into the true.