Over the last decade or so, “progressive” activists have exhibited a desire to regulate the personal behavior and values of their fellow citizens. Language, attitudes, expressions, gestures, feelings, and even thoughts are to be policed, with the aim of enforcing principles of conduct established by self-appointed “experts” in the workings of racism, sexism, classism, ableism, and other injustices.

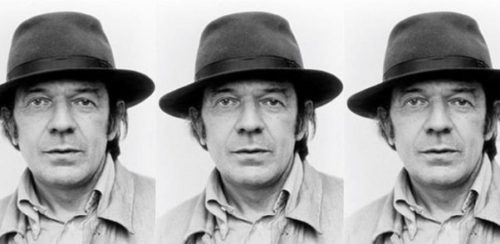

Foucault’s concept of disciplinary power might conceivably help us think about the rise of illiberalism on the progressive left. There are at least as many differences as there are similarities, however, between disciplinary power and the regulation of personal behavior pursued by activists today.

What is disciplinary power? Foucault’s view was that after the Enlightenment had undermined the moral authority of religion, modern societies developed professional and academic disciplines that purported to use scientific methods to acquire empirical knowledge of human behavior. These sciences – psychology, sociology, economics, anthropology, criminology, medicine – established how human beings normally behaved under various circumstances.

Theoretically, “normal” meant “average.” But in practice, “normal” was implicitly taken to mean “good” or “ideal.” This, Foucault argued, made possible a form of oppression that was characteristic of liberal democratic societies: individuals “internalized” the norms established by the disciplines and regulated themselves accordingly. In this way, social scientific “experts” in human behavior played the role of the earlier religious and moral authorities.