At the end of the film, Alex has agreed to publicly support the ruling party in exchange for a cushy job. Listening to Beethoven and reflecting on his good fortune, he thinks: “I was cured all right.”

The Ludovico Technique had cured Alex’s love of violence, but from his point of view the cure was worse than the disease: he thought it would get him released from prison and that he would resume his old way of life, but it left him powerless and suicidal. During the period of unconsciousness after his suicide attempt, however, brain surgeons “deconditioned” him so that hearing Beethoven’s Ninth no longer caused him to be violently ill.

That’s part of the irony of Alex’s final statement: he has been cured of the cure. But the irony is more complex, because we also see what Alex is imagining as he makes that statement.

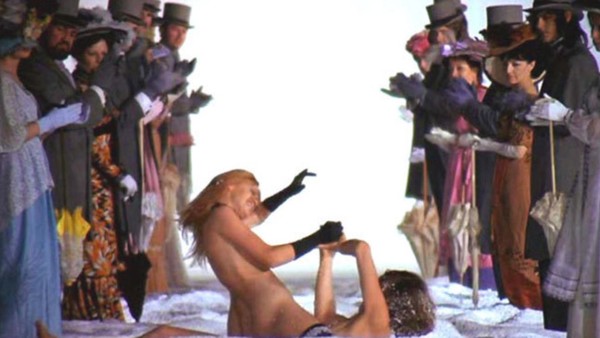

In Alex’s fantasy he lies recumbent on his back with his partner assuming a dominant position. She’s batting away Alex’s hands as he reaches for her breasts, but both are laughing and are clearly being playful. Rows of people in Edwardian dress are politely applauding.

Alex is imagining a consensual sexual act, which is obviously very different from what we’ve seen before. The fantasy should be understood in light of his deal with the government, which will take care of Alex in return for his endorsement and, presumably, his promise to abstain from violence. This now strikes him – as it would not have at the beginning of the film – as a reasonable compromise: he can resume sexual adventuring, but only with consenting adults. So long as he keeps his end of the bargain, society will approve and applaud.

It’s significant that this fantasy is accompanied by the only non-ironic (or halfway non-ironic) use of the Ode to Joy in the film. Ode to Joy celebrates the overcoming of natural human differences and the creation of a brotherhood of mankind, or the Social Contract – into which Alex has entered at last.

Of course, as the prison chaplain had pointed out, behaving in socially acceptable ways isn’t equivalent to being good. Is Alex a better person? The Minister had said that “higher morality” doesn’t matter. The point is to reduce crime, or, since this is politics, to be seen to reduce crime. From now on, Alex’s lack of virtue will be channeled into enterprises that are useful to those with power. That’s his “cure.”

We shouldn’t have sympathy for Alex, but if we do it’s because up until now, unlike the other main characters in the film, he was not in bad faith. Alex does bad things, but with a good conscience. The bad Alex was no hypocrite. In the end, though, by making a deal with the government, Alex joins in the general hypocrisy of society. This is why his cure is both triumphant and ironic: he’s become a successful hypocrite, which is all anyone ever wanted or expected of him.