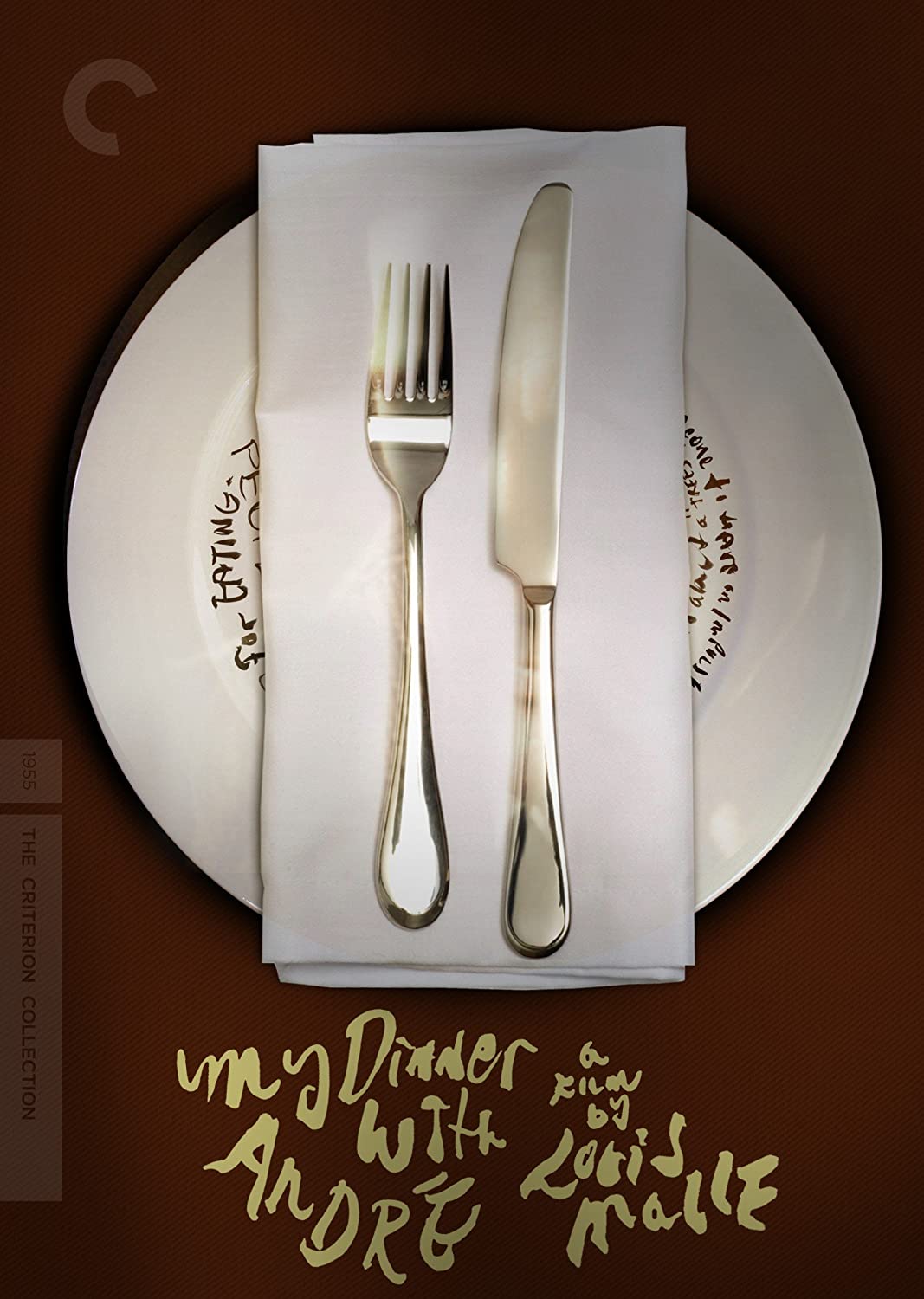

Some characterizations of My Dinner with André, 1.

Wally feels obligated to dine with André but dreads it because he has heard that André is deeply troubled and feels there is nothing he can do to help. Wally is also overwhelmed by the pressures of practical life: he can’t do anything but worry about how he will pay his bills. He settles on a solution to his immediate problem: he’ll merely ask questions of André, something he enjoys doing. That works, but in the course of his dinner with André something more happens: the meal ends with Wally a little less overwhelmed than he was when it began.

André wants to live each moment as intensely as possible, but he seems to think that this requires him to eschew any sense of a quest for larger, objective value. Wally, on the other hand, indicates that he values stable and committed relationships and his contributions, however small, to the theater, and expresses an identification with the scientific enterprise and so with a central narrative tradition of Western Civilization. But he doesn’t find many moments of passionate intensity in his day-to-day life, which, in contrast to André’s, seems to have isolated him from others. The film, narrated from Wally’s point of view, conveys his renewed appreciation for the quality of immediate experience for those with whom he shares his world. On his way home after dinner he’s noticeably more attentive to what his city means to him, and he resolves to share his experience with his girlfriend Debby.

André and Wally have different views about the meaning of life. André wants to live each moment as intensely as possible and believes that he can accomplish this by undergoing extreme experiences. Wally values stable relationships and commitments and takes pleasure accomplishing the everyday tasks they require, hoping also to occasionally contribute to the theater. As the film begins, however, Wally doesn’t take any pleasure in ordinary life and doesn’t have time to contribute to the theater. André is passionately engaged with his activities, but they don’t seem to make sense to anyone but him. Wally’s values and aims are perfectly intelligible, but he doesn’t find them fulfilling. As he listens to André’s exotic stories, Wally realizes how much he loves his life and he reminds himself of this on his way home. We’re left wondering about whether the conversation has had an impact on André.

André explains why the theater has become pointless. The method of traditional theater was to create an artificial representation of real life. It can no longer do so because real life has become artificial: people are now shallow, unfeeling, insensitive robots who merely perform their assigned roles and consume simulated experiences. You can’t simulate simulation or represent representation. We get all the fiction we need from life itself. Even if the theater were capable of representing how soulless we have become, doing so would only make people feel even more hopeless than they already do and even less inclined to look for alternatives. Wally resists this view of the theater, but he agrees that people have become superficial, artificial, insincere, and callous. André thinks that our insensitivity and artificiality were brought about by science and technology, which removed the idea of a transcendent purpose of life and led us to believe that comfort and security are the highest values. André thinks that the solution to our unreal and artificial lives is to undergo extreme experiences through which we will be “reborn.” We should live in moment and be willing to risk everything for the sake of intensity and ecstasy. Wally defends science and technology. He thinks that human beings are purposive by nature and that we can and should find fulfillment in goal-oriented activity even when the goals are ordinary everyday pleasures.

Philosophical backgrounds I: Conversation.

The word “conversation” combines the Latin con- or com- meaning “with, together” with versare or vertere meaning “to turn, bend” to form conversation, meaning literally “to turn together” or cooperate and more specifically “to live, dwell with, keep company with,” and from the 14th century “general course of actions or habits, way of conducting oneself in the world.” In the mid-16th century, the English conversation is used to mean “informal exchange of thoughts and sentiments by spoken words,” but Cicero already used conversatio to indicate private conversation among friends as opposed to public oratory. Oratory was formal and rule-governed whereas conversation obeyed conventions of politeness but not strict rules. Conversation was important in ancient Athens and Rome and was revived by Renaissance humanism because the ability to speak well with anyone was a mark of worldliness and sophistication. Politely exploring differences such that the conversation itself was more important than any of its participants was a model for moderate political life as the alternative to revolution and anarchy. This idea was central to civic humanism and civic republicanism.

Michael Oakeshott’s view of conversation is in line with this tradition. Conversation, he says, is what “distinguishes the civilized man from the barbarian.” The barbarian promotes his point of view and only his point of view, which is narrowly practical and concerned with survival and power. The civilized person is interested in the good things life has to offer beyond mere survival and other purely practical matters. He or she also understands that the search for good things shouldn’t depend on radically changing our conditions of existence. Carried too far, that would force one to live exclusively for the future and make it impossible to enjoy the present. A civilized person, Oakeshott says, “[a]ccepts the unavoidable conditions of life and makes the best of them.” One way of making the best of them is learning from one another about the good things life has to offer beyond mere survival. Conversation is the form this takes.

The qualities of conversation and the virtues of the conversationalist flow from its purpose. You mustn’t be exclusively or overly concerned with practical matters, and in particular you mustn’t insist that your personal practical concerns dominate the conversation (these are sure signs of barbarism). A conversation is personal: the words spoken are those of a speaker who takes personal responsibility for them and what they imply. The partners to a conversation must trust and respect one another (or at least act as if they do). They approach a theme in a variety of ways, informally trying out illustrations and hypotheses. They have no expectation that they will fully express themselves and come to a complete understanding of the topic or of one another, much less agree with one another. They don’t expect others to endorse their views and are prepared to fail to persuade, but they must also be willing to change their minds when it is reasonable to do so.

Oakeshott thinks that the various practices of a civilization – art, science, technology, philosophy – are ways of imagining the world. These are related to personal identity, because who we are depends on how we imagine the world. The different ways of imagining the world need to be related to one another in ways that prevent any one of them from overwhelming the others. This is done in and through conversation, the practice whereby we discuss the meaning and value of everything we do (including our conversations).

Acquiring the abilities that enable you to converse in this sense is the true purpose of education. A university houses all the “voices,” i.e. all the ways that different sorts of human beings imagine the world as they pursue the satisfaction of their desires, in such a way as to shelter the conversation among and between them. Education is an initiation or apprenticeship to the conversation; it’s not primarily acquiring knowledge of a subject. However, it cannot be formally or explicitly taught. While we are explicitly and formally mastering a subject, we are also tacitly and informally acquiring the manners, dispositions, discriminations, and other abilities required to be a good conversationalist – that is, to be a good person. Civilization, education, and conversation are ways of organizing freedom, understood as liberation from practical necessities.

To have a conversation, each partner must take the other seriously. That means not regarding the other’s views as being purely the result of ideology, history, biology, class, race, gender, etc. For a philosophical conversation at least, you must assume that your interlocutor has what he or she takes to be good reasons for believing that what he or she asserts is true. If the question were what have people thought was good, that might not be so. Empirical sciences such as history, sociology, and biology would be better. But if the question is what is good – what do we have reason to find good, which considerations count in favor of assessing something as good or right – then dialogue is the only way. It might be objected that we are able to think these things through on our own, but the plurality of possible goods counts against it. It’s unlikely that a single individual could imagine all the things that might possibly be good and all the considerations that count for and against finding them to be good. Moreover, each of us enters into a conversation with some fairly settled opinions on whatever is at issue. These opinions establish what Hans-Georg Gadamer calls a “horizon” beyond which we can’t see. As rational agents, however – as persons who can converse with each other – we’re not locked into our horizon. We can listen to others describe their horizons and in that way extend our own, accomplishing what Gadamer calls the “fusion of horizons.

Giving an account of conversation requires idealization: a statement of the ideal conditions for conversation. These conditions include the equal right and opportunity of all to introduce or criticize any proposition, and the responsibility of all to support the propositions they endorse with reasons and to make their contributions truthful, sincere, relevant, and clear. But all actual conversations take place under conditions that are less than ideal. Part of the art of conversation, therefore, is the ability to acknowledge what is less than ideal and to turn it, if possible, to conversational advantage. In actual conversation there is always the pressure of time, the imbalance of authority, and differences in manners corresponding to differences in education, class, wealth, gender, age, race, and so on. Good conversation doesn’t attempt to eliminate these differences; instead it tries to make use of them in ways that draw the participants more deeply into the conversation and commit them more fully to it. The ultimate pragmatic consideration in any actual conversation is what is most likely to keep the conversation going – or if it must be brought to an end, how to accomplish that in the most appropriate and least arbitrary way.

Seeing yourself as a moral agent involves (among other things) seeing yourself as a being that is aware of its past and anticipates its future. (By “moral agent” I mean someone who cares about living the best possible life and acts accordingly, not merely someone who tries to avoid harming others.) Another way of putting this is to say that seeing yourself as a moral agent involves seeing yourself narratively. Alasdair MacIntyre calls this the “narrative self.” According to MacIntyre, the unity of a human life is best understood as a narrative unity in which one imagines oneself as a character on a quest or journey aimed at answering the question “What is the good life?”

This quest necessarily takes place at a particular period in the history of a particular civilization, which provides the quester with inherited moral traditions that he or she takes up and which orient the quest. These traditions take the form of dramatic resources, i.e. narrated histories that convey a knowledge of available roles and their meanings, on which individuals map their personal lives to arrive at an understanding of their membership in the larger world. Since there are many such stories of the world and the people in it, one’s first moral task is to choose which of the available histories or traditions one belongs to. In the modern world this is an especially chaotic enterprise, because modernity offers a plurality of narratives that don’t add up to a unified whole. This makes moral conversation difficult in that modern individuals often encounter one another as characters in incommensurate narrative traditions, lacking in any shared criteria of evaluation that would enable them to resolve their disagreements.

Perhaps as a result, a lot of moral philosophy takes the form of trying to unify or make compatible with one another various understandings of what constitutes the good life, and I think it makes sense to look at Susan Wolf’s ideas about meaningfulness as such an attempt. Meaningfulness, she says, is a third, hitherto under-appreciated, dimension of the good life, the other two being individual happiness and morality in the relatively narrow sense of right and wrong. MacIntyre’s point would be that each of these three dimensions arose in distinct historical-moral contexts, and are encountered by modern individuals as fragmented and detached from one another. In the modern world, it’s easy for individuals to take on one fragment or dimension of a moral tradition, map their own life story on to it, and disregard equally important dimensions, to the detriment of their quest. If Wolf can make these dimensions cohere, she’ll have contributed something to making life in the modern world more morally coherent.

Philosophical backgrounds II: Meaning.

For the purpose of understanding My Dinner With André, we may approach it as a conflict between two ways of telling the story of a life corresponding to the two elements of what constitutes a meaningful life in Wolf’s sense. A meaningful life, she says, is one that’s actively and passionately engaged in projects that have objective value. To put it differently, meaningfulness arises when subjective passion is united with objective value. The idea is to contribute to something whose value is independent of your individual preferences but to which you contribute your uniquely individual talents and characteristics. Meaningfulness involves acting for “reasons of love” that contribute to enterprises that are worthy of love.

Non-philosophers probably think that the question “What is the meaning of life?” is among the central questions of philosophy. So did philosophers, for much of the history of philosophy. But in the last half of the twentieth century, most philosophers would have disagreed. The meaning of life is a question for priests and theologians, not philosophers, they would have said.

Why? For one thing, as Wolf points out, it’s difficult to say precisely what the question means, and therefore difficult to imagine what would count as an answer. The question doesn’t ask for the meaning of life in the sense that we ask for the meaning of a word. Life doesn’t refer to anything, the way words do. There is, however, another sense of “meaning.” In this sense, the question asks for the purpose of human existence. The idea is that by identifying the purpose of human life as such, we’ll learn something about how to live our individual lives.

The trouble with the question about the purpose of human life as such is that most philosophers, at least for the last century or so, have thought that there’s virtually nothing that philosophy has to say about it. If there were a God, then he might have created us for a purpose. But it’s not the job of the philosopher to find out what God’s purpose in creating us was – that’s a job for priests, theologians, and perhaps mystics. On the other hand, if there is no God then there just is no purpose of human existence, and hence no meaning in that sense. According to our modern scientific worldview, the human species is merely the result of physical processes, in particular those of evolution and natural selection.

On the other hand, as Wolf says, even atheists seem to think that lives can be more or less meaningful: they can be deeply fulfilling, or not. Although, in the absence of religious belief, it makes no sense to ask about the meaning of life, it does make sense to inquire into meaning in life. “Meaningfulness” is a feature that can be present or absent in an individual life. So, Wolf asks, what do we want when we say we want meaning in our lives? From the agent’s perspective, it seems that we want the activities that make up our lives to be fulfilling. To say that a job is meaningful, for example, is at the very least to say that it’s emotionally rewarding. But what does “meaningfulness” look like to the outside observer? Here, subjective criteria aren’t paramount. We can say that Cezanne, Einstein, and Beethoven led meaningful lives without considering how emotionally rewarding they were.

Wolf (like many others who have thought about this problem) suggests that we can make progress by trying to determine what a meaningful life is not. Here are some paradigms of a meaningless life:

• A life spent smoking pot and watching television. This is a disengaged life, unconnected to anyone or anything, going nowhere and accomplishing nothing. “Passive.”

• A life full of activity, but trivial or pointless activity. Think of David Wiggins’s pig farmer who buys more land to grow more corn to feed more pigs to buy more land to grow more corn to feed more pigs. “Pointless.” (David Wiggins, “Truth, Invention, and the Meaning of Life” [1976].)

• Someone engaged in a project that ultimately fails. For example, a physicist who spends her career working on a unified field theory and realizes towards the end of her life, when it’s too late to do anything about it, that she had taken an approach that couldn’t possibly have succeeded. Maybe such lives aren’t meaningless, but, as Wolf says, it wouldn’t be out of order to wonder if they were. And arguments that they could be meaningful might tell us something about what meaningfulness in life is. “Failed.”

On this basis, Wolf thinks that she can define meaningfulness. In contrast to Passive, a person who lives a meaningful life is actively engaged. In contrast to Pointless, this is active engagement in something that is worthy of engagement – something that has objective value. In contrast to Failed, you have to be successful, at least to some degree. Thus, a meaningful life is one that is actively and at least somewhat successfully engaged in a project that has objective value.

Qualifications:

• The term “project” can suggest some finite or limited task: the creation of a poem, the design of a product, the formulation of a mathematical proof. But other kinds of activities can also contribute to meaningfulness. So take “project” to mean not only explicitly goal-oriented activities but other ongoing activities and involvements as well.

• The phrase “active engagement” means more than just activity: one can actively carry out tasks that don’t much matter to one. To be actively engaged is to identify with your activities and to see them as at least part of what your life is about.

• And there’s more to say about the stipulation that the projects must have “objective value.” It may be difficult to establish what has objective value. But whatever we think has objective value should correlate with what we find meaningful, and whatever doesn’t have objective value should correlate with what we find to be not meaningful.

Although it may be difficult to agree on what is objectively valuable, the point is that we can’t avoid excluding merely subjective value as a sufficient condition for meaningfulness. To say merely that a meaningful life is one of active engagement in projects that seem to the one living that life to have objective value blurs the difference between having an interest in living a life that feels meaningful and having an interest in living a life that really is meaningful.

If you suspect that this is a distinction without a difference – that a meaningful life just is a life that seems meaningful to the one living it – consider a thought experiments. In Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974) Robert Nozick writes:

Suppose there was an experience machine that would give you any experience you desired. Super-duper neuropsychologists could stimulate your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book. All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain. Should you plug into this machine for life, preprogramming your life’s experiences? […] Of course, while in the tank you won’t know that you’re there; you’ll think that it’s all actually happening. […] Would you plug in? (42-43.)

Nozick argues that most people would (and everyone should) answer No. To see why, consider two possible worlds. In World 1, you’re in love with X, X is in love with you, and both of you are happy. In World 2, you’re in love with X, but X hates you, wants you only for your money, and constantly cheats on you, but, because you’re unaware of this, your experience is exactly the same as in World 1. If it doesn’t matter whether your experience corresponds to reality, then there’s no reason to prefer World 1 to World 2. Yet World 1 is plainly superior to World 2. Why? Because subjective experience accords with objective reality. You don’t just think that X is in love with you, X really is in love with you.

By the same token, to care that your life is meaningful is to care that your life is actively and at least somewhat successfully engaged in projects that not only seem objectively valuable, but that really are. It means caring that at least part of your life is devoted to something that is objectively good, that at least some of the things you love are worthy of love.

Assuming that Wolf’s theory of meaningfulness in life is correct, is there any good reason for people to want meaning in their lives? Why should someone care whether he or she is actively engaged in an objectively worthwhile project? The key element of this question is why contributing to something of objective value should matter. Wolf’s answer is that wanting to be involved in activities that have objective value is a way of facing up to the fact that you’re not the center of the universe and that your life can and will be assessed from perspectives that are not yours alone.

Recognizing one’s place in the universe, and of the independent existence of the universe, involves a recognition of the arbitrariness of your point of view. It involves recognizing the existence of a perspective from which your subjective preferences and states are matters of indifference. From this point of view, a life devoted only to your subjective values seems unjustifiably solipsistic. To live egotistically, Wolf says, is express the belief that only your happiness matters. But how could your happiness be all that matters when there are so many other things going on in the universe?

The idea is that we can have a reason to care about something, not because of our desires, but because of a fact about the world. The fact is that each of us is a speck in a vast value-filled universe, while taking yourself as the only measure of what’s valuable, flies in the face of this fact. By devoting yourself to things that have value independently of you, you implicitly acknowledge your place in the world, and your conduct is more in line with the facts.

Some philosophers draw a different conclusion from the fact that we are tiny specks in a vast universe. They say it implies that life is absurd. The idea is that a life can be meaningful only if it can mean something to someone – and not just anyone, but someone other than oneself, and indeed someone of more intrinsic or ultimate value than oneself. Anyone, these philosophers say, can live a life that matters to someone else. But if that person has no more objective importance than you have, he or she can’t supply meaning to you. If each life is individually lacking in meaning, then the totality of all lives must also be meaningless.

These philosophers would say that in acknowledging the smallness of my perspective, I must also acknowledge the smallness of everyone else’s perspective. According to this view, if the lives of one or two people don’t amount to much of anything, then neither do the lives of one or two million or billion. But Wolf thinks that this is a misunderstanding. These philosophers think that we want to matter, but we don’t (and can’t) matter, so our lives are absurd. It’s true, Wolf concedes, that in the context of the universe as a whole, we don’t matter. But we can live in a way that harmonizes with the fact that we don’t matter. Learning to value things whose importance is independent of our subjective relation to them is a way of trying to acknowledge this condition. For a life to meaningful, there have to be distinctions of value – distinctions between what’s objectively valuable and what is not. If one activity is objectively worthwhile and another isn’t, then one has reason to prefer the former whether or not anyone else knows or cares.

A meaningful of life is one that exhibits active involvement in an objectively valuable project. However, these two conditions can and do come apart. A life can be full of activity, and the activities might matter greatly to the agent, yet be trivial or silly in terms of what’s objectively worthy of concern. Or it might be devoted to activities that contribute to something genuinely valuable but that don’t matter to the agent, and so fail to engage and define the agent. Getting the two together, or moving towards getting them together, is one measure of progress towards living a meaningful (and to that extent good) life. It’s a reasonable basis for a narrative moral quest.

The film.

Is it also a way of describing the narrative structure of My Dinner With André? André represents one way in which Wolf’s two conditions can come apart: he’s passionately engaged, but in activities that are subjectively valuable to him alone. Wally represents the other condition: he’s committed to things that matter, but he’s not passionately engaged.

The idea is that André has been living in what Kierkegaard calls the “aesthetic” realm of “lower immediacy.” He wants to live each moment as intensely as possible, but he seems to think that this requires him to eschew any sense of a quest for larger, objective value. Wally, on the other hand, indicates that he values stable and committed relationships and his contributions, however small, to the theater, and expresses an identification with the scientific enterprise and so with a central narrative tradition of Western Civilization. But he doesn’t find many moments of passionate intensity in his day-to-day life, which, in contrast to André’s, seems to have isolated him from others. The film, as narrated from Wally’s point of view, conveys Wally’s renewed appreciation for the quality of the immediate experience of those with whom he shares his world. On his way home after dinner he’s noticeably more attentive to what his city means to him, and he shares his experience with his girlfriend Debby.

The point is that each character has enabled the other to enter into different aspect of our inherited moral narrative traditions, and in the only way possible, namely by story-telling and conversation. The film exhibits the value of conversation, not only as the medium but also as the means of moral agency. As Michael Oakeshott describes the nature and value of conversation:

Conversation … is an unrehearsed intellectual adventure. […] As civilized human beings, we are the inheritors … of a conversation, begun in the primeval forests and extended and made more articulate in the course of centuries. […] It is the ability to participate in this conversation … which distinguishes the human being from the animal and the civilized man from the barbarian. […] Education, properly speaking, is an initiation into the skill and partnership of this conversation in which we learn to recognize the voices, to distinguish the proper occasions of utterance, and in which we acquire the intellectual and moral habits appropriate to conversation. And it is this conversation which, in the end, gives place and character to every human activity and utterance. (Michael Oakeshott, “The Voice of Poetry in the Conversation of Mankind” [1959].)

Some characterizations of My Dinner with André, 2.

André, a theater director, can’t work because he feels that the theater is impotent in the modern world. Wally, a playwright, can’t work because he is overwhelmed by financial pressures. After a conversation with André at a restaurant Wally feels restored and that same evening finds himself telling Debby, his girlfriend, “all about my dinner with André.” Wally’s representation of the dinner to Debby is the first step in the creation of My Dinner with André. The film, which could just as easily have been a play, is a living refutation of André’s claim that the modern theater is impotent because it can’t simulate simulation and because showing people how bad things are will only make them more despairing. A simple conversation between two men is the least artificial dramatic form imaginable, and it is fully adequate to the task. The artificial character of modern life is represented in André’s description of it, and expressing it in conversation is more satisfying than it is despairing. As André’s presence in the film shows, Wally was able to convince André that he was wrong about the impotence of modern theater and thus made it possible for him to work again – André, like Wally, has been “restored” (albeit as an actor not a director). The existence of the film itself is the material resolution of the problems it depicts.

André has been passionately engaged in activities over the past few years, but they are activities that are valuable only to him – to Wally, and presumably to us, they seem eccentric and self-indulgent. Wally, on the other hand, is involved in an activity that is objectively valuable – the theater – but, overwhelmed by the pressures of practical life, he’s not passionately engaged in it. In André and Wally, Susan Wolf’s two conditions for meaning in life – subjective passion and objective value – have come apart. Wally and André appear to be defending two different approaches to life but in fact their attitudes represent two conditions that ought ideally to be united. By having a conversation in which they express their points of view, each has an opportunity to grasp the limits of his perspective. Even if they don’t fully succeed in doing so, we the audience, who are in a position to assess the quality of the conversation objectively, are able to.

For the last few years, André has been exploring what Søren Kierkegaard calls the “aesthetic” realm of “lower immediacy.” His primary aim in life has been to avoid boredom, and to do so he goes from one extreme or intense experience to another without committing himself to anything in particular. Although he believes he is growing spiritually and fulfilling himself, he’s actually in Kierkegaardian “despair” because he’s defined himself and his world in a way that makes it impossible to live what he takes to be an authentic life. Wally, in effect, conveys this Kierkegaardian assessment to André. In his defense, André describes himself as something like Nietzsche’s “free spirit.” He eschews unconditional commitments in favor of exploiting opportunities to take risks with the aim of strengthening and satisfying his desire to grow, treating his life as a work of art. The alternative is to sink into “herd morality” and devote oneself to comfort and security at the expense of what really matters after the death of God: becoming who you uniquely are. In reply, Wally defends a life devoted to comfort and security and claims that creative activity is possible even under those conditions.

The exchange between Wally and André begins unpropitiously. Wally dreads dining with André and decides to get through the meal by asking him questions. André regales Wally with a series of exotic and increasingly improbable tales of the spiritual adventures he had been pursuing for the previous few years. Until the middle of the dinner (the middle of the dinner, not the middle of the film) we are listening in on an interview, not a conversation: Wally merely listens to André talk, occasionally nodding to indicate understanding if not interest or agreement. A turning point takes place when the main course, the cailles aux raisins, is served and André confesses that he’s disgusted with himself. Now Wally becomes genuinely interested and actively presses André for an explanation – though their exchange remains essentially an interview. Eventually, however, as André becomes more explicit about his values and his assessment of the modern world, Wally mounts a criticism of André’s position and defends an alternative of his own. André isn’t persuaded, but he takes Wally seriously and attempts to find common ground as well as to reply to his objections. In the end they agree on the basically mysterious character of human existence and the difficulty of fully understanding or mastering the human predicament. The viewer understands that it is only at this moment that the conditions required for an authentic conversation have been established – but the restaurant is closing and the conversation must end.

See also:

Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method (1960).

Paul Grice, “Logic and Conversation” (1957).

Jurgen Habermas, “Discourse Ethics: Notes in a Program of Philosophical Justification” (1990).

Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (1981, 1985).