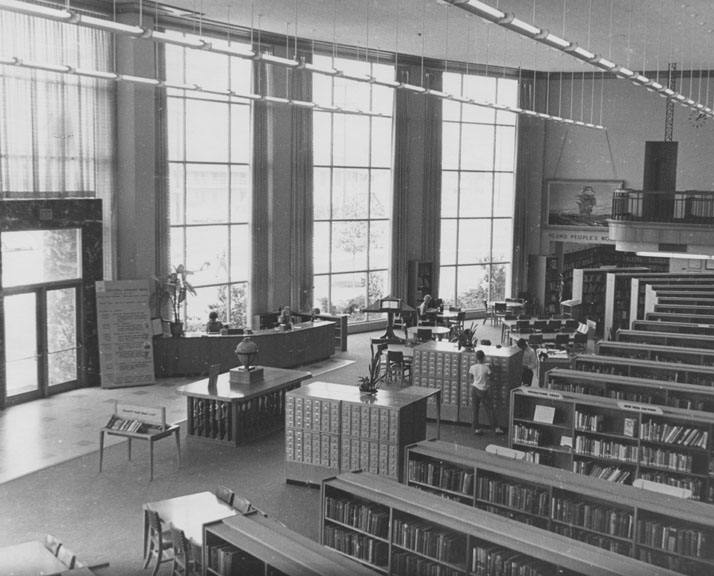

Late in 1971, when I was 16, during a visit to the Santa Ana Public Library (in Southern California), I had a dramatic aesthetic experience.

At this point I had read fairly widely. I knew Hawthorne, Twain, Thoreau, Whitman, and Melville, Kafka and Sartre, Huxley and Orwell (Down and Out in Paris and London as well as Animal Farm). I’d read (or read at) Russell and Wittgenstein, Nietzsche, Marx, and Freud, and people like B.F. Skinner, Buckminster Fuller, Arthur Koestler, Lewis Mumford, Marshall McLuhan, Tom Wolfe, and Joan Didion. I’d seen paintings by Picasso and heard Stravinsky, Wagner, and Morton Subotnick.

I was always on the lookout for more, though I didn’t always have a clear idea of what I was looking for.

That afternoon in 1971, however, I did know. I had come for a copy of Molloy, which I wanted to read after having seen a PBS broadcast called Beginning to End in which the Irish actor Jack MacGowran, dressed in a thick black cloak, stands in the Mojave Desert and recites passages from the works of Samuel Beckett.

I found the desired volume in the card catalogue, noted its location in the stacks, followed the letters and numbers down the rows of books, and soon reached the Becketts. But for some reason I took down How It Is instead of Molloy. The Grove Press edition had a white cover with black and red lettering that repeated the book’s author and title in contrasting fonts and sizes. Beckett’s prose was virtually formless – “past moments old dreams back again or fresh like those that I pass or things things always and memories I say them as I hear them murmur them in the mud” – and though what I held in my hands was clearly some kind of novel, it was unlike any I had ever imagined. I was so overwhelmed that my knees buckled and I sat down on the floor between the stacks to continue reading.

The novel conveys the thoughts of an unnamed narrator, engulfed in mud, unable to orient himself, barely able to crawl, dragging a sack filled with a few cans of food and a can opener, who encounters a being called Pim. The text, without punctuation, crawls across the page with as much grace as the narrator slogs through the mud. Who Pim was, we never learn, and as the story goes on it seems more than possible that he never really existed. Given what happens to him, one hopes he didn’t. Even so, the apparent encounter allows the narrator to give a minimal structure to his sojourn in the muck: “before Pim,” “with Pim,” and “after Pim.”

Over the next weeks and months I read everything else of Beckett’s I could find: Watt, Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable, and the plays – Waiting for Godot, Endgame, Krapp’s Last Tape, Happy Days. During this time, The Lost Ones appeared. Beckett was alive! Somehow, it hadn’t occurred to me that this was possible. I continued to follow his work until his death in 1989.

At the center of all this was the feeling that struck me immediately upon looking into How It Is. It was aroused by Beckett’s tone, which was icy and ascetic, far removed from ordinary life, but also intimate and at times surprisingly comforting and sympathetic. Through it, I made emotional contact with a world in which understanding is not fully achieved, in which communication, if it happens at all, is indirect, and in which events occur but do not cohere. How It Is is not a pleasant read – the events it describes, or fails to describe, are cruel almost beyond imagination. It’s very far from my favorite Beckett work. But the voice I heard in it had a value that was independent of its themes.

A year or so later I found a similar aesthetic at an exhibit organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It was a retrospective of the work of Bruce Nauman, who was still only in his 30s at the time. The works on display seemed to have little or nothing to do with one another: homemade neon signs, low quality black-and-white videotapes of someone walking in circles or pulling on his lips, brightly lit corridors one could barely squeeze through, a steel cage, photographs of spilled coffee, crude models of body parts such as hands, arms, and ears, artless wax and concrete casts, and written proposals for works left undone. Intention, motive, form, and content were utterly opaque, yet there was something irresistibly intriguing about the atmosphere created by the work. I felt uncannily at home and ended up spending the whole day there.

Ironically, I met and briefly befriended another, similarly engrossed visitor and we spent hours discussing the work. I never saw her again.

What Beckett and Nauman evoked was a feeling for the depth and richness of the phenomenon of intelligibility. Whatever else we’re doing, we’re making sense of things – or failing to make sense of them. What are the conditions of sense-making? What have we made when we’ve made sense? Of what value is it?

Below, Bruce Nauman, Self-Portrait of the Artist as a Fountain, 1966.